Authors:

Dr Claudia Barber, M.D. and Dr Jordi Serra, M.D.

Digestive System Research Unit. University Hospital Vall d’Hebrón, Barcelona, Spain. Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd)

Introduction

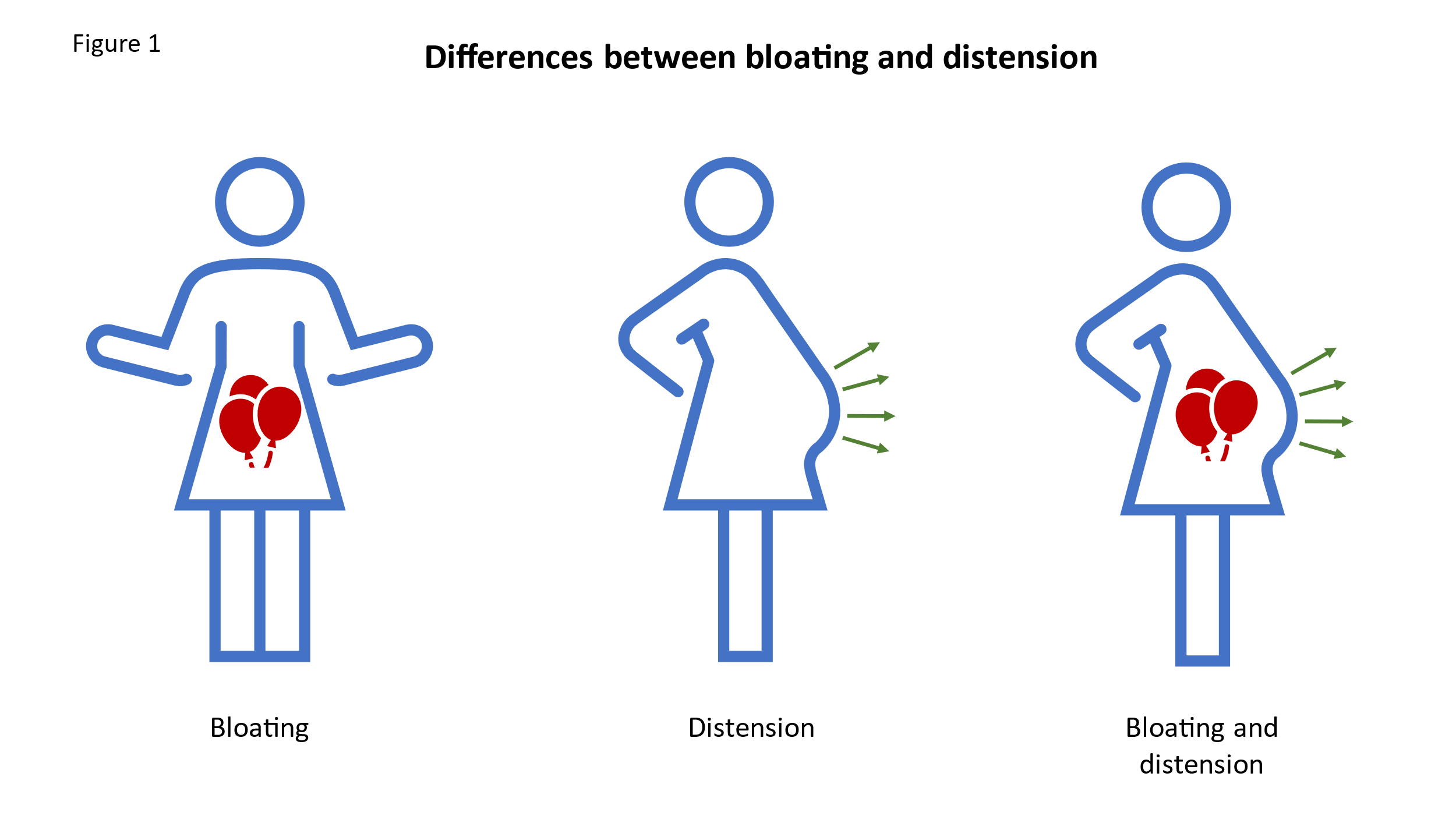

Bloating is one of the most frequently reported symptoms in gastroenterology consultations. The Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study has shown that up to 18% of the global population experiences bloating or abdominal distension (1). However, bloating and distention are much more prevalent (>50%) when associated with other Disorders of Gut Brain Interaction (DGBI), such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), constipation, and functional dyspepsia (2). It is important to distinguish between bloating and distension. Bloating refers to the subjective sensation of fullness, abdominal pressure or trapped gas, whereas abdominal distension describes an objective increase in abdominal girth. Nevertheless, in a high proportion of patients, both symptoms occur concurrently (3,4). (Figure 1)

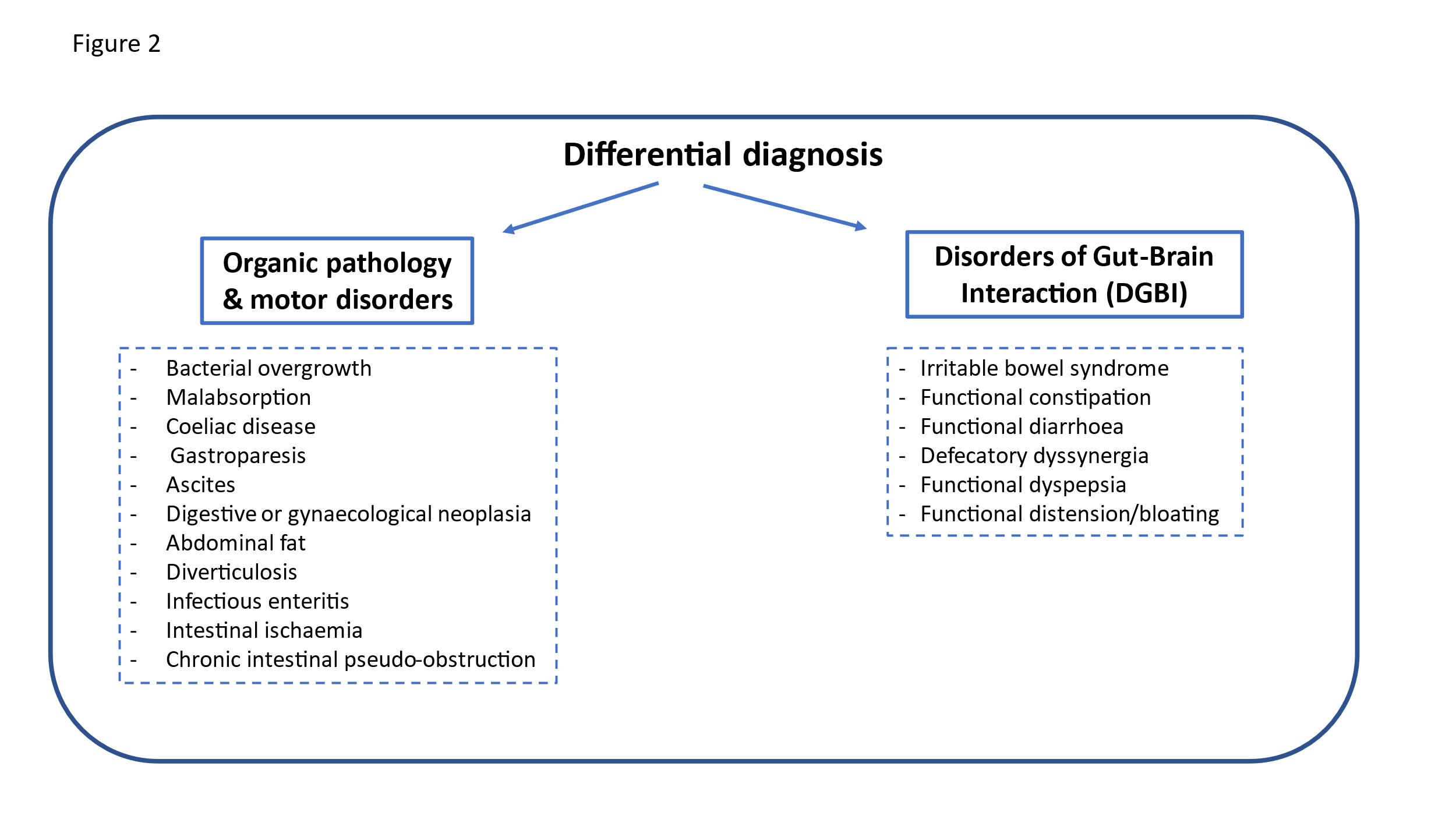

Bloating and abdominal distension may have either a functional or an organic origin; therefore, the clinical approach to patients presenting with these symptoms should include the exclusion of organic disease and consideration of the various pathophysiological mechanisms that may contribute to the condition.

Clinical presentation and case

The patient is a 54-year-old woman, with no relevant past medical history other than a family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative. Her obstetric history includes two spontaneous vaginal deliveries, both without instrumental assistance. She presents with a two-year history of abdominal distension that fluctuates throughout the day, accompanied by a sensation of bloating. The symptoms are occasionally triggered by the consumption of dairy products and partially improve following bowel movements. Additionally, she reports diffuse abdominal pain, which worsens with bloating and is relieved by defaecation. Her symptoms are exacerbated by stress.

She describes a recent change in bowel habits, with a reduced frequency (one bowel movement every 48-78 hours) and a change in stool consistency (Bristol Stool Chart types 1-2), without any visible blood. These symptoms are accompanied by significant straining during defaecation and a sensation of incomplete evacuation, occasionally requiring digital manoeuvres for assistance. The patient has increased her dietary fibre intake and has used an osmotic laxative, but with no noticeable improvement. She also reports a weight gain of approximately 8 kilograms over the past 4-6 months.

On examination, the patient was noted to be obese, with visible abdominal distension, and increased abdominal adiposity. Digital rectal examination revealed a paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter during straining, with no other abnormal findings.

Investigations and management

The first step is to complete the medical history in order to rule out the presence of alarm symptoms that may suggest an underlying organic condition. In this patient, the recent change in bowel habits, age over 50, and a family history of gastrointestinal malignancy are considered red flags. These should be investigated further with appropriate testing, including laboratory analyses such as full blood count, thyroid function tests, and coeliac serology, which is relevant in the context of the IBS-type symptoms (pain and altered bowel habits) reported by the patient. A colonoscopy is also indicated(5,6).As epithelial ovarian cancer typically presents in postmenopausal women and may manifest with abdominal pain and distension, it should be excluded by means of serum cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing or transvaginal ultrasonography (7,8).

Once organic pathology has been excluded, it is important to consider concomitant conditions that may contribute to bloating, such as constipation and lactose intolerance. A two-week trial of lactose elimination may be considered. Furthermore, dietary modifications, such as reducing the intake of insoluble fibre and avoiding fermentable laxatives should be recommended.

In patients with dyssynergic defaecation (a condition characterised by a lack of coordination of the pelvic floor muscles during defecation, leading to chronic constipation, and other symptoms such as excessive straining during defecation and a sensation of incomplete evacuation, blockade and the use of digital manoeuvres to aid defecation), constipation and abdominal distension may improve with biofeedback therapy (9,10). Therefore, defecatory dyssynergia should be excluded by means of anorectal manometry, and, if confirmed, treated accordingly with biofeedback.

Recent studies have shown that patients with functional abdominal distension may suffer from abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia, which involves an abnormal response of the abdominal wall muscles and the diaphragm to minor increases in intra-abdominal contents. This condition can be reversed using specific biofeedback techniques aimed at retraining the abnormal abdomino-phrenic response. While earlier approaches utilised sophisticated electromyography or plethysmography biofeedback protocols (11,12), recent studies have demonstrated that a simplified non-instrumental technique can also be effective in reversing this condition . Using original audiovisual material and hands-on guidance from a trained practitioner, patients are taught the mechanism of distension and how to relax the diaphragm while contracting the abdominal wall. Practical courses on this specific technique are currently being held, allowing it to be disseminated and implemented in clinical consultations.

In our patient, a reduction in fibre intake combined with biofeedback therapy to address dyssynergic defaecation led to an improvement in bowel function; all laxatives were discontinued, and abdominal distension was alleviated. In addition, dietary advice was provided to support weight reduction.

Learning points

- The first step in assessing a patient with bloating is to obtain a comprehensive medical history and conduct a physical examination, with the aim of ruling out any red flag symptoms suggestive of an underlying organic cause.

- Once organic pathology has been excluded, it is important to identify any associated symptoms, such as constipation or specific food intolerances, which may contribute mechanistically to the development of bloating, and, when present, to manage these appropriately.

- After addressing potential aetiological mechanisms, the management of bloating should focus on dietary and lifestyle modifications, reduction of intraluminal content, and, in patients with visible abdominal distension, treatment of abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia.

Discussion

Bloating and abdominal distension may be manifestations of a Disorder of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) or of an underlying organic disease (Figure 2) (13). A thorough history and physical examination are essential to evaluate the different aetiopathogenic mechanisms involved. Diurnal variation in distension, exacerbating or relieving factors such as fasting and/or food intake, the relationship to bowel movements, perceived food intolerances, associated gastrointestinal symptoms, and psychological comorbidities all suggest a functional origin of symptoms.

By contrast, the presence of warning signs such as blood in the stool, recent changes in usual bowel habits, unintentional weight loss, symptom onset after the age of 50, anaemia and/or nutritional deficiencies, palpable masses on examination, fever, and a personal or family history of cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or coeliac disease, point towards an organic aetiology (14) (Figure 2). In addition, the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recommended that female patients, especially those older than 50 years, who develop abdominal pain, persistent abdominal distension and pelvic or abdominal pain should undergo measurement of serum cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) concentrations as a secondary screen.

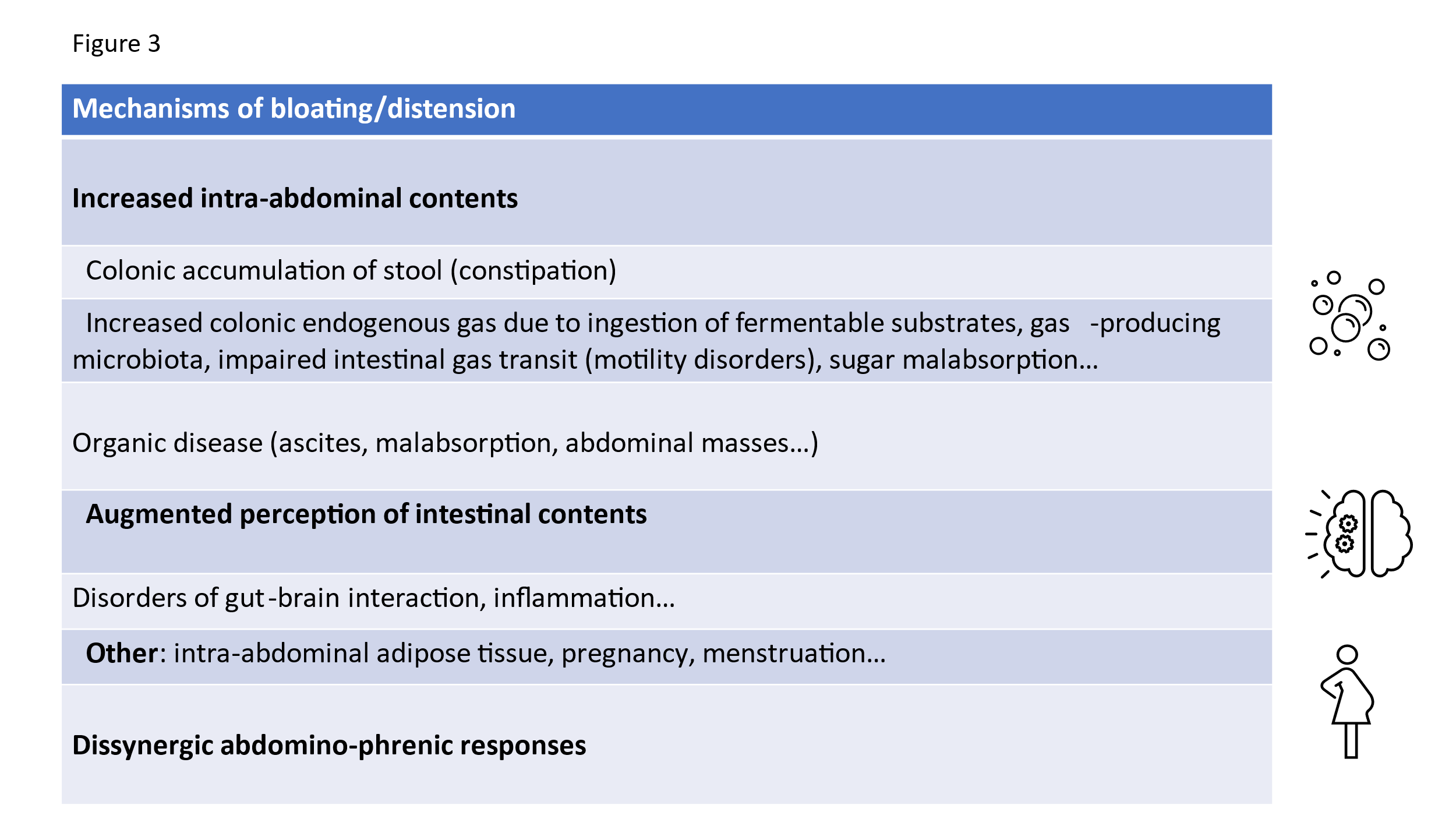

Once major organic pathology has been excluded, patient management should consider whether abdominal distension is an isolated symptom or part of another functional disorder that may play a pathophysiological role and requires specific attention (3). In our patient, bloating is associated with abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for constipation- predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Other factors to consider include a possible lactose intolerance and weight gain (Figure 3).

The first step in the management of patients with bloating is to provide dietary and lifestyle advice. In the case of our patient, with suspected lactose intolerance, an empirical restriction of lactose for a short period (2 weeks) may be initially implemented. The management of constipation should also be reassessed. Insoluble fibre may exacerbate bloating symptoms and offer limited relief in patients with IBS. Therefore, dietary recommendations and the selection of laxatives should avoid excessive fermentation that could worsen the sensation of bloating (17). A low FODMAP diet (low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) has demonstrated beneficial effects on bloating (18). However, long- term restrictive diets may lead to nutritional deficiencies and should be reserved for patients who are refractory to other treatments, under the strict supervision of a nutritionist or dietitian (19,20).

Another strategy to reduce gas production involves decreasing gas-producing bacterial species and/or modifying their metabolic activity through prebiotics, probiotics and antibiotics. However, objective evidence of clinical efficacy remains limited (18,21). As shown in some studies, prebiotics may worsen bloating during the initial weeks but could improve symptoms over time (22). Rifaximin, a non-absorbed antibiotic, is a medication used in the treatment of IBS-D, with different levels of recommendation according to the guidelines (23). It has been proven to be superior to placebo for the management of bloating (24,25) and it is the most studied antibiotic, with the strongest scientific evidence supporting its use as treatment for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). However, it is important to note that the role of SIBO in abdominal distension is controversial. In patients without predisposing factors such as severe alterations in intestinal motility or anatomical changes in the digestive tract, bloating and abdominal distension do not have the ability to predict its existence, meaning that initiating diagnostic investigation of SIBO based solely on the presence of these symptoms does not seem justified, especially considering the low sensitivity and specificity of the breath test that are usually employed for this diagnosis (16). The use of rifaximin for IBS/SIBO without constipation is unlicensed in UK but could be considered off label in people with refractory symptoms.

In our patient, the treatment of constipation was crucial for the final outcome. It has been reported that abdominal symptoms such as bloating, pain, discomfort, and cramping are common in patients with dyssynergic defecation and improve after biofeedback therapy (9,10). Therefore, in patients with abdominal distension who complain of constipation that does not improve with laxative treatment, defecatory dyssynergia should be excluded and, if present, treated through re-education of the defecatory manoeuvre with biofeedback. Prokinetics and secretagogues may be considered in patients who fail to respond to the former measures.

Linaclotide, a secretagogue that increases intestinal secretion and decreases visceral sensitivity, has been shown in placebo-controlled studies to reduce bloating associated with constipation (18).

Visceral hypersensitivity has been linked to abdominal pain and bloating, and both antispasmodics and neuromodulators have been shown to improve abdominal pain in patients with IBS. However, their effects on bloating and distension remain unclear (26).

Recent studies have indicated that functional abdominal distension is caused by an abnormal response of the abdominal wall muscles and the diaphragm to small increases in abdominal contents (11,12). This disorder, known as abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia, can be reversed using advanced biofeedback techniques (27). Currently, a new treatment strategy using non-instrumental feedback is being developed to improve access to this therapy forthe majority of patients (personal data).

Conclusion

Abdominal distension is a prevalent condition in gastroenterology that affects the general well-being and quality of life of patients. Several mechanisms can cause abdominal distension, including increases in abdominal contents, altered sensitivity and altered viscero-somatic responses to normal gut stimuli. An approach that considers the different characteristics of bloating, abdominal distension, and concomitant symptoms can guide a therapeutic strategy aimed at addressing the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in these symptoms in each specific patient.

Author Biographies

CME

Masterclass: Narcotic Bowel Syndrome

10 February 2025

Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction

28 October 2024

- Ballou S, Singh P, Nee J, Rangan V, Iturrino J, Geeganage G, et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Bloating: Results From the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep 1;165(3):647-655.e4.

- Moshiree B, Drossman D, Shaukat A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Evaluation and Management of Belching, Abdominal Bloating, and Distention: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep 1;165(3):791-800.e3.

- Barber Caselles C, Aguilar Cayuelas A, Yáñez F, Alcala-Gonzalez LG. Abdominal distension and bloating: Mechanistic approach for tailored management. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 May 1;47(5):517–21.

- Lacy BE, Cangemi D, Vazquez-Roque M. Management of Chronic Abdominal Distension and Bloating. Vol. 19, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021.

- Rao SSC, Ozturk R, Laine L. Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: A systematic review. Vol. 100, American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005. p. 1605–15.

- Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 May 1;150(6):1393-1407.e5.

- Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA. Ovarian cancer. Vol. 384, The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group; 2014. p. 1376–88.

- Lugata J, Shao B, Makower L, Rapheal A, Mremi A, Mchome B. Management of a large uterine fibroid arising from the cervical stump following subtotal hysterectomy causing massive abdominal distension. A rare case report and review of the current literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2024 Sep;122:110160.

- Agrawal A, Houghton LA, Reilly B, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Bloating and distension in irritable bowel syndrome: The role of gastrointestinal transit. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009 Aug;104(8):1998–2004.

- Baker J, Eswaran S, Saad R, Menees S, Shifferd J, Erickson K, et al. Abdominal symptoms are common and benefit from biofeedback therapy in patients with dyssynergic defecation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul 30;6(7).

- Villoria A, Azpiroz F, Burri E, Cisternas D, Soldevilla A, Malagelada JR. Abdomino-Phrenic Dyssynergia in Patients With Abdominal Bloating and Distension. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011 May;106(5):815–9.

- Accarino A, Perez F, Azpiroz F, Quiroga S, Malagelada J. Abdominal Distention Results From Caudo-ventral Redistribution of Contents. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2009 May;136(5):1544–51. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016508509001735

- Malagelada JR, Accarino A, Azpiroz F. Bloating and Abdominal Distension: Old Misconceptions and Current Knowledge. Vol. 112, American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017.

- Malagelada JR, Accarino A, Azpiroz F. Bloating and Abdominal Distension: Old Misconceptions and Current Knowledge. Vol. 112, American Journal of Gastroenterology. Nature Publishing Group; 2017. p. 1221–31.

- Ovarian cancer: recognition and initial management Clinical guideline [Internet]. 2011. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg122

- Alcedo González J, Estremera-Arévalo F, CobiánMalaver J, Santos Vicente J, Alcalá-González LG, Naves J, et al. Common questions and rationale answers about the intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SIBO). Gastroenterologia y Hepatologia. EdicionesDoyma, S.L.; 2024.

- Serra J, Pohl D, Azpiroz F, Chiarioni G, Ducrotté P, Gourcerol G, et al. European society of neurogastroenterology and motility guidelines on functional constipation in adults. Vol. 32, Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2020.

- Serra J. Management of bloating. Vol. 34, Neurogastroenterology and Motility. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2022.

- Bek S, Teo YN, Tan XH, Fan KHR, Siah KTH. Association between irritable bowel syndrome and micronutrients: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;37(8):1485–97.

- Whelan K, Martin LD, Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE. The low FODMAP diet in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: an evidence-based review of FODMAP restriction, reintroduction and personalisation in clinical practice. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018 Apr;31(2):239–55.

- Malagelada JR, Accarino A, Azpiroz F. Bloating and Abdominal Distension: Old Misconceptions and Current Knowledge. Vol. 112, American Journal of Gastroenterology. Nature Publishing Group; 2017. p. 1221–31.

- Barber C, Sabater C, Ávila-Gálvez MÁ, Vallejo F, Bendezu RA, Guérin-Deremaux L, et al. Effect of Resistant Dextrin on Intestinal Gas Homeostasis and Microbiota. Nutrients. 2022 Nov 1;14(21).

- Papale AJ, Flattau R, Vithlani N, Mahajan D, Nadella S. A Review of Pharmacologic and Non-Pharmacologic Therapies in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Current Recommendations and Evidence. Vol. 13, Journal of Clinical Medicine. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024.

- Sharara AI, Aoun E, Abdul-Baki H, Mounzer R, Sidani S, Elhajj I. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Feb;101(2):326–33.

- Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, et al. Rifaximin Therapy for Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome without Constipation A BS T R AC T. Vol. 364, n engl j med. 2011.

- Keefer L, Drossman DA, Guthrie E, Simrén M, Tillisch K, Olden K, et al. Centrally Mediated Disorders of Gastrointestinal Pain. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 19;

- Barba E, Accarino A, Azpiroz F. Correction of Abdominal Distention by Biofeedback-Guided Control of Abdominothoracic Muscular Activity in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2017 Dec 1;15(12):1922–9.