Authors:

Chithra Mohan - Department of Gastroenterology, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Sailish Honap - Department of Gastroenterology, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK, School of Immunology and Microbial Sciences, King’s College London, UK

Conflicts of Interest

CM has no conflicts to declare.

SH served as a speaker, a consultant, an advisory board member, and/or has received travel grants from Pfizer, Janssen, Alphasigma, AbbVie, Galapagos, Takeda, Lilly, Ferring, and Pharmacosmos.

INTRODUCTION

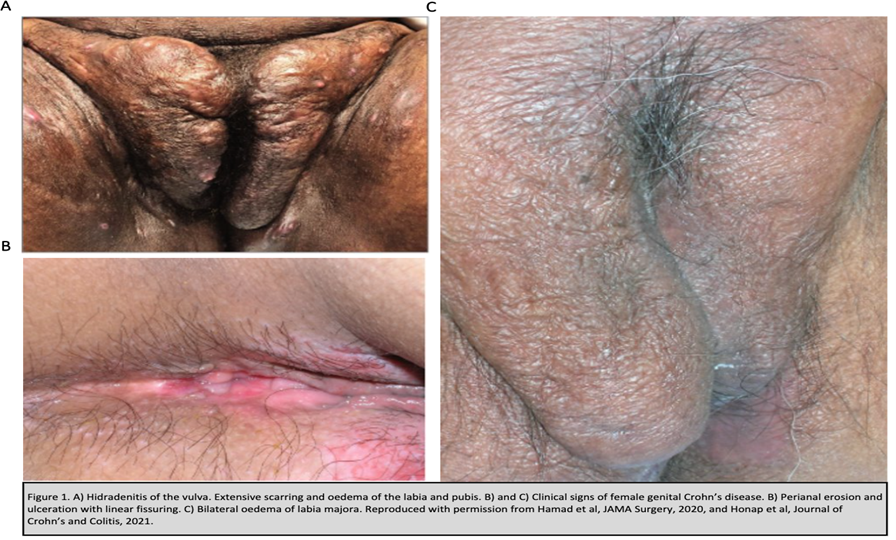

Crohn's disease (CD) is an immune-mediated, inflammatory disease characterised by a transmural granulomatous inflammation and progressive gut damage. Extraintestinal manifestations are common and affect up to one third of patients with CD and of these, up to 40% affect the skin.1,2,Metastatic CD is a dermatological extra-intestinal manifestation and a rare cutaneous form of CD and these lesions are typically non-contiguous from gastrointestinal tract. The term Genital Crohn’s disease (GCD) is used when there is involvement of external genitalia in this context. The true incidence or prevalence of GCD are unclear as there are only a few small case series and cohort studies published, and it is difficult to assess the epidemiology.3 The heterogeneous clinical presentation of GCD combined with lack of experience in managing this rare entity by clinicians may often result in misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), or acne inversa, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition, which primarily affects intertriginous and apocrine gland-bearing areas, such as the axillae, inframammary, and inguinal folds. This debilitating condition follows a chronic relapsing course, and the primary event is thought to be driven by follicular occlusion of the folliculopilosebaceous unit.4 The global prevalence of HS is estimated to be 1-4% 5 and is characterised by a range of skin lesions, including deep-seated nodules and abscesses, sinus tracts or fistulae, and fibrotic scars.

Clinically, GCD and HS may be difficult to differentiate, particularly if HS affects the inguinal and anogenital regions or in the presence of perianal disease. This results in cross specialty referrals, diagnostic delays, and the lack of a unifying diagnosis can lead to significant psychological distress and physical morbidity for the patient. The aim of this article is to provide a brief overview for gastroenterologists in the diagnosis and management of this rare manifestation of CD.

CLINICAL FEATURES & DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Most cases of GCD are reported from late teenage years to the second and third decade of life and no gender predominance has been identified.3 The median age of presentation is 16 years for males and 29 years for females from the published literature.3 Fifty percent of patients with GCD have a pre-existing diagnosis of luminal CD and 20-30% of cases are subsequently diagnosed with luminal CD on endoscopy.

In female GCD, the most common features are genital oedema, ulcers (typically knife-cut linear ulcerations) and fissures, and hypertrophic lesions. Less commonly, symptoms such as dyspareunia, abscess formation, hyperpigmentation and perianal involvement are reported. In males, the predominant features are genital oedema (affecting the penis mostly but scrotum also) and erythema. Other features include perianal skin tags, ulcers/fissures, erectile dysfunction, abscesses, and hypertrophic lesions.

HS typically presents in the second to fourth decade of life and the prevalence tends to fall after 50 years of age.6 Western studies show female preponderance and a more severe disease course in males.7 The lesions in HS typically start as deep subcutaneous nodules in anatomical areas of apocrine glands such as axillary folds, groin, perineal, perianal and infra-mammary regions. These nodules rupture discharging foul smelling mucopurulent fluid and form tender dermal abscesses. This natural course of HS lesions is particularly useful to differentiate from GCD. Chronicity and relapsing symptoms are hallmarks of HS and with time, the lesions progress to recurrent abscesses, sinus tracts, fibrosis, and permanent scarring.4 The lesions of HS and GCD are difficult to differentiate even in expert hands and diagnosis of GCD can be challenging especially in the absence of GI symptoms or a pre-existing luminal CD diagnosis.

Table 1: Differential diagnosis for GCD and HS

Diagnosis | Investigations |

| Travel and sexual history, stool tests, genital swabs, specific immunohistochemistry |

| Sputum MCS and AFB, TB IGRA, serum ACE, chest imaging |

| Presence of skin and oral lesions, HLA B51, autoimmune and vasculitis panel, histology |

| Association with IBD and inflammatory arthropathy, characteristic rapid tender ulceration of papule, vesicle or pustule, histology |

| Focussed clinical history, histology |

LINKS BETWEEN HS & IBD

The association between HS and IBD has been an area of interest in both gastroenterology and dermatology communities. Both HS and CD share many similarities. First, their pathogenesis and pathophysiology are underpinned by genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation and dysbiosis. Second, they have numerous overlapping clinical features, including both having an increased prevalence of spondyloarthritis. Finally, a proportion of patients in both conditions respond well to TNF alpha inhibitors.

There is a significant association between HS and IBD.8 Patients with HS had a 2.12 fold increased odds of developing CD and 1.51 increased odds to develop ulcerative colitis. Conversely, the incident rate ratio of HS in IBD was 8.9.9

INVESTIGATIONS

All suspected cases of GCD should be referred for specialist gastroenterology and dermatology opinions, with those that have an expertise in genital skin diseases and IBD, respectively. There are no treatment guidelines for this rare manifestation. The diagnosis of GCD requires comprehensive clinical assessment and a series of investigations to exclude key differentials (table 1). Cross-sectional imaging is important – an MRI pelvis is needed to evaluate the extent and characteristics of sinus/fistula tracts as well as involvement of anal sphincter complex and may help differentiate from HS. An MRI small bowel is important to look for concurrent CD or assess CD in those with known small bowel involvement. Imaging may reveal rectal wall thickness, local lymphadenopathy, ulcerations, fistulas and bowel involvement. An ileocolonoscopy with histology is important to look for/re-evaluate luminal CD. Even in the absence of luminal symptoms, a full evaluation with these investigations is recommended as up to 25% of patients may have occult disease.3 A skin biopsy is commonly performed for vulval CD but less so for penile CD.3 Granuloma and chronic inflammatory infiltrates are key histological features.

HS is predominantly a clinical diagnosis. A full body examination is required to assess the site, extent and severity of skin lesions. Less often, histological assessment may be required to confirm diagnosis. Common histological findings include follicular occlusion, perifolliculitis, follicular epithelial hyperplasia and follicular hyperkeratosis.10

MANAGEMENT

Management of both GCD and HS requires a holistic and multidisciplinary approach. Patient education and counselling are of paramount importance, especially given the huge psychosocial impact on patients. HS has a strong association with metabolic syndrome and modifiable risk factors such as obesity, and diabetes mellitus must be addressed. Smoking cessation should be strongly advocated in both conditions and support should be offered.

In GCD, systemic antibiotics, systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus and biologic therapies have been tried with variable success rates. The most promising results come from TNF alpha inhibitors from reported case series so far and therefore it is advised that all efforts to achieve therapeutic drug levels such as escalated dosing and/ or addition of concomitant immunomodulator to reduce immunogenicity must be made. Good responses to ustekinumab have also been reported in a few cases.11 Surgery may be required in selected patients.

The first line treatment for HS is usually a prolonged course (6-12 weeks) of systemic antibiotics along with topical antiseptics. In moderate to severe cases, TNF alpha inhibitors have shown good efficacy in RCTs. Both adalimumab and infliximab are currently used in the UK and recently bimekizumab, an IL-17A and IL-17F inhibitor has been licensed for moderate to severe HS.12 It is crucial to exclude CD before considering bimekizumab for HS as there are reports of new IBD diagnosis or worsening of pre-existing IBD in patients treated with bimekizumab.13 Patients who do not respond to standard medical management may require surgical interventions such as deroofing, simple excisions, laser therapy or ablative electrosurgery.

LEARNING POINTS

- GCD, although a rare clinical entity, causes considerable physical and psychological morbidity to the young population.

- Early recognition of GCD and prompt treatment with advanced therapies is crucial.

- GCD and HS have overlapping clinical, genetic and immunological features. Recommend low threshold to screen HS patients who have GI symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Danzi JT . Extraintestinal manifestations of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Intern Med1988;148:297–302.

2. Thrash B , Patel M, Shah KR, Boland CR, Menter A. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol2013;68:211.e1–33; quiz 244–6.

3. Honap S, Meade S, Spencer A, et al. Anogenital Crohn’s Disease and Granulomatosis: A Systematic Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Treatment. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2022;16:822–34. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab211

4. Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105–15. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S111019

5. Bukvić Mokos Z, Markota Čagalj A, Marinović B. Epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:564–75. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.08.020

6. Gb J, M H, Nh N. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;35. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90321-7

7. Shih T, Seivright JR, McKenzie SA, et al. Gender differences in hidradenitis suppurativa characteristics: A retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:672–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.07.003

8. Chen W-T, Chi C-C. Association of Hidradenitis Suppurativa With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatology. 2019;155:1022–7. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0891

9. Yadav S, Singh S, Varayil JE, et al. Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.173

10. Smith SDB, Okoye GA, Sokumbi O. Histopathology of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:251–7. doi: 10.3390/dermatopathology9030029

11. Stoleru G, Robbins G, Papadimitriou JC, et al. Rapid Resolution of Vulvar Crohn’s Disease With Ustekinumab. ACG Case Rep J. 2020;7:e00452. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000452

12. Kimball AB, Jemec GBE, Sayed CJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of bimekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa (BE HEARD I and BE HEARD II): two 48-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre phase 3 trials. The Lancet. 2024;403:2504–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00101-6

13.Gordon KB, Langley RG, Warren RB, et al. Bimekizumab Safety in Patients With Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Pooled Results From Phase 2 and Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Dermatology. 2022;158:735–44. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1185

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

Dr Chithra Mohan

Dr Chithra Mohan is a Gastroenterology and Hepatology registrar at St George’s Hospital (London).

Dr Sailish Honap

Dr Honap is a Consultant Gastroenterologist at St George’s University Hospital (London) with a subspecialty interest in inflammatory bowel disease. He completed initial postgraduate training in Birmingham, higher specialty training in London, and a post-CCT IBD fellowship in Nancy (France). He is completing a doctoral thesis at King’s College London, where he is studying the response predictors of JAK inhibition in ulcerative colitis and maintains a close collaborative link with the IBD Institute at Nancy University Hospital (France) as an honorary research fellow.