Learning points

- Understanding the relevance of colonoscopic surveillance in IBD patients

- Surveillance interval recommendations

- Methods for colonoscopic surveillance

- Management of dysplasia

- The future of colonoscopic surveillance

Key words

- Colorectal Cancer

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Dysplasia

- Surveillance

- Image enhanced endoscopy

Abbreviations

CRC – colorectal cancer, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, UC – ulcerative colitis, PSC – primary sclerosing cholangitis, HD – high definition (colonoscopy), SD – standard definition (colonoscopy), WLE – white light endoscopy, IEE – image enhanced endoscopy, CE – chromoendoscopy, VCE – virtual chromoendoscopy, EMR – endoscopic mucosal resection, ESD – endoscopic submucosal dissection

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer in the UK. When diagnosed at an early stage, one-year survival is extremely favourable at 98% compared with 44% in those diagnosed late1. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are at an increased risk of CRC which accounts for 10%-15% of deaths in IBD2. Colonoscopic surveillance can detect precursor lesions or early neoplasia, removal of which may prevent development of CRC3.

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) has published guidelines on stratifying IBD patients’ CRC risk4 . Variation in colonoscopic surveillance strategies exists and regular endoscopic surveillance places a significant burden on services and more importantly on patients5. The future of IBD-CRC surveillance may need to incorporate non-endoscopic methods to assess risk to ensure the right patients are getting the right procedure at the right time.

Why should IBD patients undergo colonoscopic surveillance?

IBD patients are at an increased risk of developing CRC; recent large population studies showed overall adjusted hazard ratios of 1.66 (95% CI 1.57–1.76) and 1.40 [95% CI 1.27, 1.53] in UC and Crohn’s patients respectively compared with the general population6,7 . CRC is likely to be detected earlier in IBD patients undergoing regular surveillance translating into a better prognosis3.

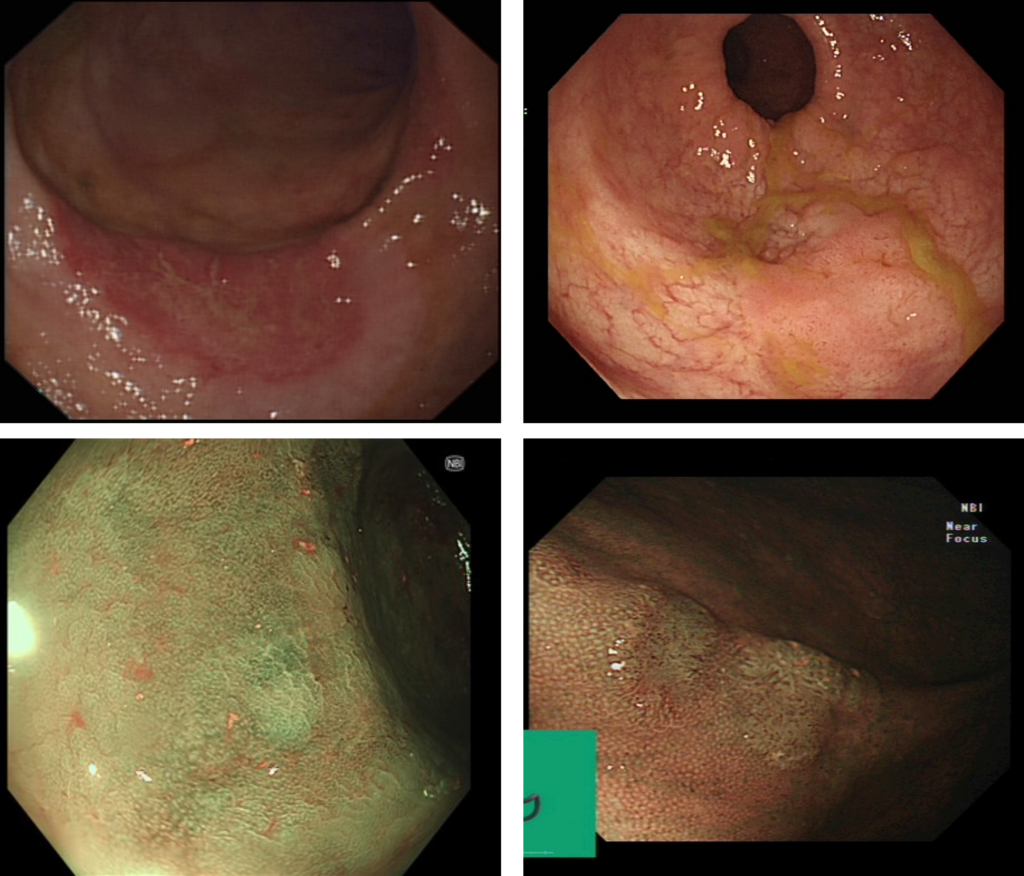

The key factor driving carcinogenesis in IBD is chronic mucosal inflammation. IBD-CRC progresses through the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence, although unlike sporadic CRC the transition from normal tissue to low and high-grade dysplasia and finally CRC is not always stepwise2 . Dysplasia is often detected in flat mucosal abnormalities that are less easily vualised than adenomatous polyps (see examples figure 1). In the UK, the 3-year post colonoscopy CRC (PCCRC) rate is more than three times higher in IBD patients than non-IBD patients8. Despite improvements in PCCRC overall, this key performance indicator has remained stubbornly high for IBD patients. This finding is in keeping both with the difficulty in detecting IBD-dysplasia and the accelerated carcinogenesis of IBD-CRC9.

These features suggest that a more tailored approach to surveillance in IBD-CRC is required.

When should surveillance be carried out?

Recognising risk factors for CRC in IBD patients is crucial in guiding surveillance recommendations. Disease severity and extent have consistently been shown to be independent risk factors for CRC in UC; extensive disease carries the highest risk of CRC, and those with proctitis have no increased risk compared with the general population10. Other risk factors include young age at onset, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), colonic strictures, pseudo-polyposis, previous IBD-associated dysplasia and a family history of CRC4.

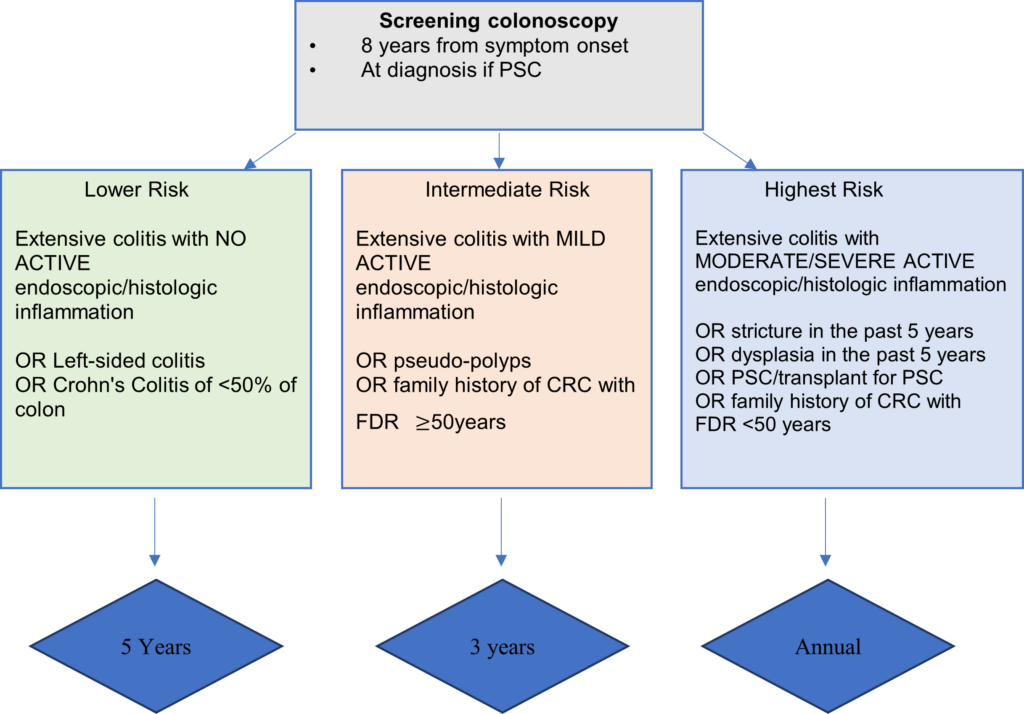

BSG guidelines4 risk-stratify into sub-groups which determines surveillance intervals (figure 2). Age, sex and certain life-style factors that may also play a role in the risk of CRC development11 are not included in this risk assessment.

Surveillance procedures should ideally be undertaken during periods of quiescent disease with effective bowel cleansing regimens to minimise the risk of a missed cancer diagnosis8,12.

How should surveillance colonoscopy be conducted?

Historically dysplasia was thought to be macroscopically invisible. As a result, guidelines recommended an extensive biopsy protocol in which multiple random biopsies from each colonic segment. With improved endoscopic resolution, most cases of dysplasia in IBD are now visible endoscopically13. The SCENIC consensus guidelines published in 2015 strongly recommend high-definition (HD) over standard-definition (SD) colonoscopy when using white light. The addition of image-enhanced endoscopy, particular in the era of HD-colonoscopy, has proven more controversial14.

Image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) has been extensively explored in IBD surveillance due to the predominance of subtler, flat lesions. Chromoendoscopy (CE) utilises a blue dye (methylene blue or indigo carmine) while virtual chromoendoscopy (VCE) is an electronic imaging technique. Both provide contrast enhanced images of the mucosal surface15.

There are a large amount of data comparing IEE to WLE alone; however, only the more recent studies included HD-colonoscopy. The SCENIC group recommended the use of CE and considered HD-chromoendoscopy the ideal surveillance method14. The universal adoption of CE is limited by lack of availability, the quality of bowel preparation required and the cumbersome method of application. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) updated their guidance in 2019 to recommend that either CE or VCE could be utilised in IBD surveillance16. On the basis of more recent data17,18. Rabinowitz et al 19 suggest that CE, VCE and WLE are all acceptable modalities, provided HD-scopes are available to an endoscopist adequately trained in dysplasia detection using the modality of choice.

The utility of non-targeted biopsies in the era of advanced endoscopic imaging has long been contested20. In one randomised controlled trial of 246 patients with UC >7 years duration, the proportional yield of dysplasia detection was significantly higher in the targeted biopsy group (6.9% [24 of 350]) than in the random biopsy group (0.5% [18 of 3725]; P < .001)21. However, despite their low yield, random biopsies may be useful in high-risk patients19. The ESGE recommend that when CE or VCE is employed, in experienced hands during quiescent disease activity, non-targeted biopsies can be forsaken but should be considered in patients with a personal history of colonic neoplasia, tubular-appearing colon, strictures or PSC16.

Flat lesions and background inflammation/pseudo-polyposis make the optical diagnosis of IBD dysplasia uniquely challenging. Although there is no data to support this, it seems logical for endoscopists with expertise in IBD dysplasia detection to perform surveillance on dedicated lists. As there are no validated training programs ESGE advise self-learning via on-site training of at least one-week’s duration with an expert and at least 20 procedures with histological feedback from targeted biopsies. The expert panel defined proficiency as a dysplasia detection rate of >10%22.

Management of dysplasia

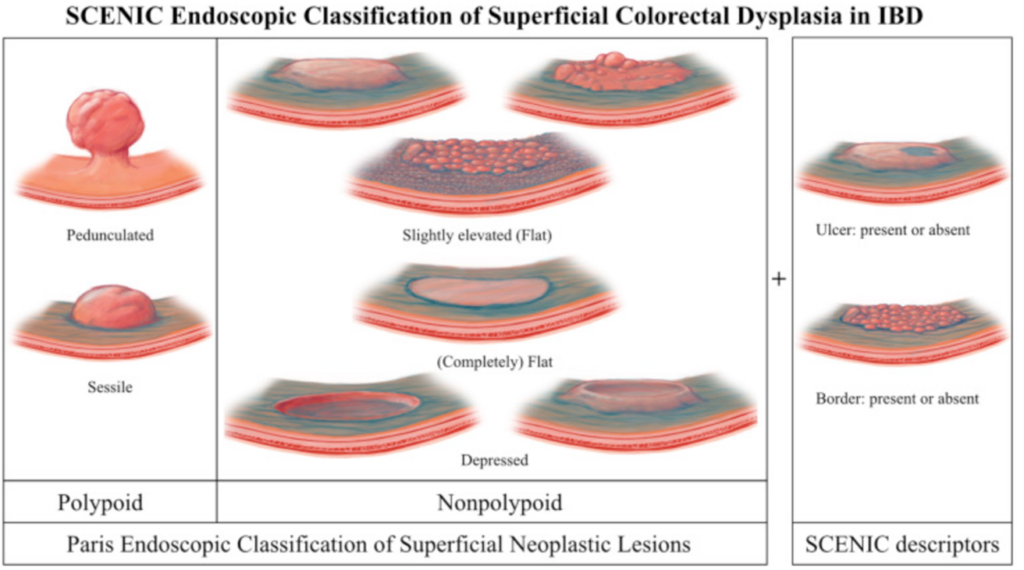

Endoscopic resectability of a pre-neoplastic lesion is the most important predictor in determining the risk of progression to CRC; the distinction between a sporadic adenoma or dysplasia associated lesion/mass is less relevant12. The SCENIC group developed the Modified Paris classification of visible lesions14 (figure 3) which is used to guide endoscopic management. With advancements in endoscopic therapy, including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), fewer patients need surgical intervention. In cases of invisible dysplasia, the procedure should be repeated by an endoscopist with expertise in IBD surveillance. If no visible lesion is detected management should be on a case-by-case basis19. The Ulcerative Colitis-Cancer Risk Estimator (UC-CaRE) is a useful providing an estimated risk of progression from low grade dysplasia to CRC23. This also supports patients to have a more active role in shared decision making.

What next?

Surveillance techniques are rapidly evolving as technology changes with most recent data suggesting that VCE, CE and HD-WLE are currently all acceptable methods. Recommendations for standardised IBD colonoscopy reporting have been made and their adoption should improve overall quality24. Artificial intelligence is likely to become part of our armamentarium in the near future. As IBD therapy improves, the burden of regular colonoscopic surveillance is growing. Further work is needed to develop strategies to target surveillance to patients at highest risk of dysplasia and cancer and minimise surveillance in low-risk and co-morbid patients in whom dysplasia or CRC is unlikely to occur in their estimated lifetime. Molecular biomarkers are emerging as a novel method to optimise risk stratification to be more personalised25. Comprehensive management should involve a multi-disciplinary team strategy as well as empowering IBD patients to have a prominent role in decision-making regarding their care.

Summary

| Surveillance Onset | 8 years from diagnosis/symptom onset At diagnosis in PSC |

| Surveillance Interval | 1, 3 and 5 yearly as per BSG risk stratification |

| Surveillance Modality | WLE, CE or VCE if HD-colonoscope by experienced endoscopist CE favoured over SD-WLE |

| Biopsy Protocol | Targeted biopsies sufficient if: -HD-WLE/CE/VCE employed -Adequate bowel preparation -Quiescent disease -Endoscopist trained in dysplasia detection -No high-risk features (PSC, tubular colon, strictures, personal history of colonic neoplasia) |

| Management of visible dysplasia | Multi-disciplinary team approach involving advanced endoscopist, colorectal surgeon and IBD expert Endoscopic methods include EMR and ESD |

| Management of invisible dysplasia | Repeat colonoscopy by IBD expert using image enhanced HD endoscopy If truly invisible; colectomy or enhanced surveillance can be offered. Shared-decision making with patient is encouraged |

Table 1: Summary of IBD CRC Surveillance; onset, interval, modalities, management and follow-up based on recent guidance and expert opinion as discussed in main body of text4,16,19,22.

Figure 1: Examples of endoscopic images of IBD-associated dysplasia under standard white light endoscopy (top panel) and narrow band imaging (bottom panel).

Figure 2: Surveillance recommendations for patients with Colitis. Adapted from updated BSG IBD Guidelines4.

Figure 3: Modified Paris Classification of Visible lesions14.

Author Biographies

Dr Julia Louisa Gauci MD MRCP (UK)

Julia Gauci is a specialist trainee in gastroenterology in South-East Scotland. She completed her MD, with distinction, at the University of Malta in 2014. She is a co-editor for the Scottish Society for Gastroenterology ‘Digest This!’ webinars. She currently embarking on an advanced endoscopy fellowship in Westmead Hospital Sydney, with a focus on tissue resection techniques and third space endoscopy.

Dr R A Speight MA (Cantab) MBBS (hons) MD MRCP (Gastro)

Ally Speight is a consultant gastroenterologist and IBD lead at the Newcastle upon Tyne NHS trust. He is a graduate of Girton College, Cambridge (Natural Sciences, Genetics) and completed his MBBS, with honours, at Newcastle University in 2005. He completed specialty training in gastroenterology in North East England. He subspecialises in IBD and was awarded an MD by Newcastle University for his research in metabolic signalling pathways in Crohn’s disease in 2015. He has a clinical interest in IBD, coeliac disease and GI complications from oncology treatments. His research interests include therapeutics in IBD and IBD associated cancers. He is a PI on several commercial trials and investigator led, portfolio studies in IBD. He was awarded an NIHR Greenshoots award in 2017. He is a member of the BSG IBD Committee and helped draft the BSG position statement on immune checkpoint inhibitor colitis and various IBD guidelines.

Dr Laura Jane Neilson MBChB MD MRCP (Gastro)

Laura Neilson is a consultant gastroenterologist at South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust. She completed specialty training in the North East of England. She has active research interests in patient experience of endoscopy, endoscopy quality and early detection and prevention of colorectal cancer and is PI on various national studies. She was awarded an MD by Newcastle University in 2019 for developing a patient-derived patient reported experience measure for endoscopy (Newcastle ENDOPREM). She is now leading research adapting the PREM for various procedures, including capsule endoscopy, hepatobiliary procedures and international translation. Laura is an elected member of the BSG Endoscopy Committee and co-chairs the Northern Region Endoscopy Group (NREG).

Dr Shahida Din BMSc MBChB PhD FRCP (Edinburgh)

Shahida Din is a Consultant Gastroenterologist at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh and a Research Clinician leading a scientific programme identifying factors predictive of IBD associated colorectal cancer. Shahida was awarded a PhD in 2014 by the University of Edinburgh on research describing modulation of aberrant molecular signalling pathways improving the efficacy of cancer therapies. In 2021, Shahida was appointed to lead a Scottish Government working group to standardise IBD Surveillance practices. In 2019, was jointly awarded a Helmsley Charitable Trust Grant to develop the Crohn’s Disease Gut Cell Atlas with her collaborators in Edinburgh and Cambridge. Shahida is a member of the BSG IBD Committee, Gastroenterology specialty advisor to the RCPE and MHRA Gastroenterology, Rheumatology, Immunology and Dermatology Panel. Shahida is passionate about sharing good clinical practices and mentoring the next generation of gastroenterologists.

CME

Oral Ulceration and Diarrhoea

22 April 2024

How I investigate abnormal liver function test in a patient with IBD

09 January 2024

Where do small molecules fit in IBD?

13 December 2023

- Cancer Research UK. Bowel Cancer Research Statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-Zero. (2021).

- Dyson, J. K. & Rutter, M. D. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: what is the real magnitude of the risk? World J. Gastroenterol. 18 29, 3839–3848 (2012).

- Bye, W. A., Nguyen, T. M., Parker, C. E., Jairath, V. & East, J. E. Strategies for detecting colon cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2017) doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000279.pub4.

- Christopher A. Lamb1, 2*, Nicholas A. Kennedy3, 4, T. R. et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut (2019).

- Denters, M. et al. Patients’ perception of colonoscopy. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 25, (2013).

- Olén, O. et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet 395, 123–131 (2020).

- Olén, O. et al. Colorectal cancer in Crohn’s disease: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 475–484 (2020).

- Burr, N. E. et al. Variation in post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer across colonoscopy providers in English National Health Service: population based cohort study. BMJ 367, l6090 (2019).

- Porter, R. J., Arends, M. J., Churchhouse, A. M. D. & Din, S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Colorectal Cancer: Translational Risks from Mechanisms to Medicines. J. Crohn’s Colitis 15, 2131–2141 (2021).

- Beaugerie, L. et al. Risk of colorectal high-grade dysplasia and cancer in a prospective observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology (2013) doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.044.

- Wijnands, A. M. et al. Prognostic Factors for Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 160, 1584–1598 (2021).

- Rutter, M. D. Mistakes in colonoscopic surveillance in IBD and how to avoid them. UEG Education 2021; 21 26–28 https://ueg.eu/a/279 (2021).

- Rutter, M. D. et al. Most dysplasia in ulcerative colitis is visible at colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 60, 334–339 (2004).

- Laine, L. et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81, 489-501.e26 (2015).

- Iacucci, M. et al. Advanced endoscopic techniques in the assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: new technology, new era. Gut 68, 562 LP – 572 (2019).

- Bisschops, R. et al. Advanced imaging for detection and differentiation of colorectal neoplasia: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2019 VO – 51 RT – Journal Article. Endoscopy OP – C6.

- Bisschops, R. et al. Chromoendoscopy versus narrow band imaging in UC: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Gut 67, 1087 LP – 1094 (2018).

- El-Dallal, M. et al. Meta-analysis of Virtual-based Chromoendoscopy Compared With Dye-spraying Chromoendoscopy Standard and High-definition White Light Endoscopy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Increased Risk of Colon Cancer. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 26, 1319–1329 (2020).

- Rabinowitz, L. G., Kumta, N. A. & Marion, J. F. Beyond the SCENIC route: updates in chromoendoscopy and dysplasia screening in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. 95, 30–37 (2022).

- Hu, A. B., Burke, K. E., Kochar, B. & Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Yield of Random Biopsies During Colonoscopies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Undergoing Dysplasia Surveillance. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27, 779–786 (2021).

- Watanabe, T. et al. Comparison of Targeted vs Random Biopsies for Surveillance of Ulcerative Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 151, 1122–1130 (2016).

- Dekker, E. et al. Curriculum for optical diagnosis training in Europe: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy 52, 899–923 (2020).

- Curtius, K. et al. Multicentre derivation and validation of a colitis-associated colorectal cancer risk prediction web tool. Gut 71, 705 LP – 715 (2022).

- Devlin, S. M. et al. Recommendations for Quality Colonoscopy Reporting for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results from a RAND Appropriateness Panel. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 1418–1424 (2016).

- Baker, A.-M. et al. Evolutionary history of human colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gut 68, 985 LP – 995 (2019).